A Rare Low Latitude Auroral Event

A Rare Low Latitude Auroral Event

“Auroras are not supposed to behave like this at this latitude.”

Oosterbeek, where I live, is located at approximately 51.98 degrees north. This is a latitude where auroral activity is normally limited to faint glows low on the northern horizon, if it is visible at all. Clear overhead structures, distinct auroral bands, and a full auroral dome belong to far northern regions, not to a suburban field in the Netherlands surrounded by light pollution.

But on the 19th of January 2026, the sky ignored those rules.

Driven by a severe geomagnetic storm, the aurora unfolded in a way that is rarely observed at nearly 52 degrees north.

Around 22:00 CET (21:00 UTC), the aurora borealis became visible in the Netherlands. This was not a subtle display or a faint glow near the northern horizon, but the result of a strong geomagnetic storm. A full auroral dome expanded from the north toward the east and west, with structured bands forming directly overhead.

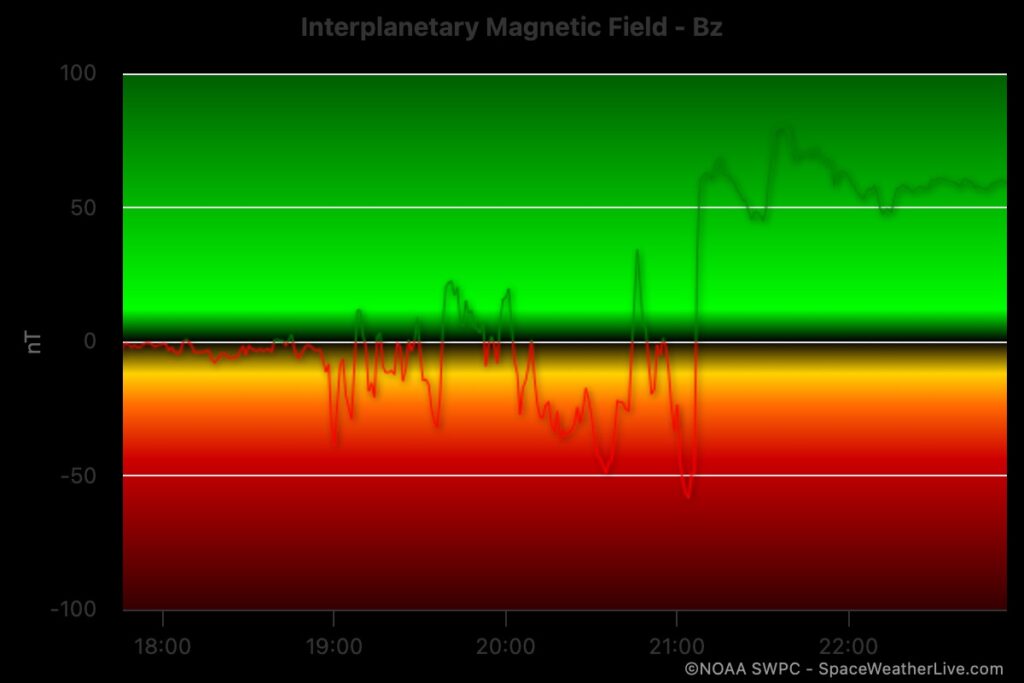

When the aurora alerts on my phone went off, the parameters immediately stood out. The storm reached KP8, while the interplanetary magnetic field Bz component dropped to nearly minus 60 nT. For a location at 51.98 degrees north, this combination is highly significant. At such latitudes, visible aurora generally requires both a high planetary KP index and a strongly southward oriented Bz. This enables efficient magnetic reconnection between the solar wind and Earth’s magnetosphere.

Under these conditions, energy transfer into the magnetosphere is maximized. The KP index is a global measure of geomagnetic activity and reflects the severity of disturbances in Earth’s magnetic field. Such geomagnetic storms are caused by intense solar activity, often associated with large-scale solar eruptions that inject magnetized plasma into the solar wind. At the same time, the interplanetary magnetic field was strongly southward oriented, with Bz values near minus 60 nT. This combination allows solar wind energy to couple efficiently with Earth’s magnetosphere, causing the auroral oval to expand far equatorward. As a result, structured aurora, including overhead arcs and visible color, become possible at lower latitudes where they are normally absent.

Despite the exceptional data, I was not particularly hyped when I stepped outside. I was more curious than excited. My front garden borders almost directly on a cornfield, with a recently renovated house standing just beyond it. I thought that if there was any auroral activity at all, I might at least capture a quiet atmospheric image of the house silhouetted against a faint green glow.

I am well acquainted with the aurora. I have traveled multiple times to the high north and have seen nearly every form it can take. I have also photographed auroras in the Netherlands before. Typically, this means a weak diffuse glow near the northern horizon, sometimes accompanied by narrow vertical rays, often referred to as spears. At approximately 52 degrees north, anything beyond that would be very unusual.

As I reached the edge of the cornfield, I immediately sensed something was different. The northern sky was clearly illuminated and glowing through breaks in the cloud cover. I set up my camera and took a test shot. That was the moment everything changed.

The entire sky was lit.

Even with a 24 mm lens on a full frame camera, I could not capture it all in a single frame. Standing partially beneath the trees, I looked around in disbelief. Through the branches, I noticed a pale haze forming. This was clearly not cloud cover. This was not supposed to be happening, right? I raised my camera and took a quick handheld shot.

The image came back green.

At that moment, it became clear what was happening. An auroral band was forming directly overhead. I moved quickly into the open field, away from the trees, and there it was. An arc stretching across the sky above me.

My mind completely exploded.

I was standing in an open field, surrounded by light pollution, without a carefully chosen composition. Yet I was witnessing a structured auroral arc overhead from my own front yard in Oosterbeek. Seeing this at 51.98 degrees north, far equatorward of the typical auroral oval, felt deeply unreal and overwhelming.

As the band slowly dissolved, I continued walking. In the distance stood a large high voltage transmission tower, and behind it the sky turned deep red. This red emission was visible to the naked eye. Under normal circumstances, such high altitude auroral emissions are too faint to be perceived visually and are usually only detectable photographically. The exceptional intensity of the storm made them unmistakable without photographic aid.

At that moment, I found myself torn between two choices. I could stay and shoot what I could, or move to a location where I could position myself better.

Walking back toward my car, I ran into a few neighbors. I explained what they were seeing, and we spoke briefly. During that time, the red glow intensified even further. Out of urgency, I took a few quick shots before running to the car.

But where to go?

The skyline of Arnhem crossed my mind, but the light pollution there would likely overwhelm any remaining structure. The railway bridge was another option. I had captured a strong aurora image there two years earlier, and despite that familiarity, it remained the safest and most predictable choice. I decided to go there.

About twenty minutes later, barely paying attention to the road and constantly scanning the sky for renewed activity, I arrived at the railway bridge. Other aurora watchers were already present. I immediately moved away from them to set up my camera, aligning the North Star precisely above the bridge. Based on past experience, this alignment offered the best chance of capturing any remaining auroral structure centered above it.

The moment I took the first image, I knew the peak had passed.

The intensity had dropped significantly. The glow was still present, but there were no bands, no structure, and no visible motion. I checked the data. The Bz had swung sharply into positive territory, reaching plus 60 nT. Again, an extreme value, but one that effectively suppresses further auroral development by reducing energy coupling into the magnetosphere.

I waited for another hour, taking a few atmospheric images and hoping for a resurgence that never came. By around 00:30 CET (23:30 UTC), with a full workday ahead, I packed up and headed home.

I have photographed the aurora many times in far northern regions, but seeing it unfold directly overhead from my own front yard was something entirely different. It was a brief, unexpected, and likely once in a lifetime experience.

Comments are closed.